It has been reported that the color of the container affects the taste of the beverage. For example, if you drink a café au lait from a white container, it will taste more bitter than if you drink it from a blue or transparent container. Also, research results have shown that coffee or chocolate drinks in orange or brown containers have a stronger coffee or chocolate taste. However, in these studies, only specific beverages were used, and it was unclear whether the effect of the color of the container on taste was only for specific beverages or for other beverages. In addition, since the taste intensity was assessed while the beverage itself was directly visible, the perceived effect was either caused by the color of the container alone or by interactions such as the contrast between the color of the beverage itself and the color of the container. It was unclear.

Figure 1: Containers for each color condition used in the experiment. A transparent PET bottle was wrapped in a tube of colored drawing paper so that the aqueous solution could not be seen directly.

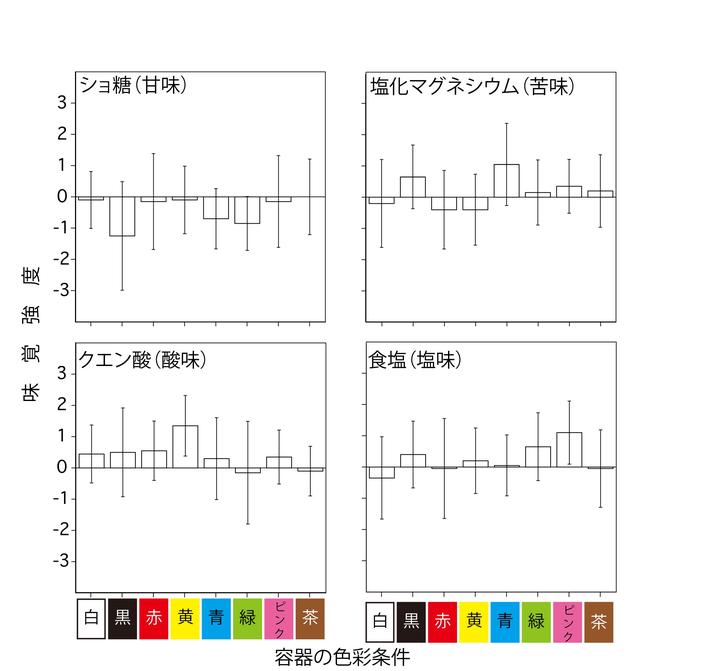

In this study, we used four aqueous solutions (sucrose, magnesium chloride, citric acid, and salt) in which one of the four basic tastes (sweet, bitter, sour, and salty) was stronger, and the colors of the containers (white, black, and red). , yellow, blue, green, pink, and brown). This time, the cylindrical container was completely wrapped in colored paper to make the beverage itself invisible (Fig. 1). In order to examine the effect of the color of the container, the experiment participants held each aqueous solution with a straw in their mouths when they saw what color it was with their eyes open and when they closed their eyes with an eye mask. , bitterness, sourness, and saltiness were evaluated on an 11-level scale. Then, using the intensity of taste evaluated under the closed-eyes condition as a reference, we examined the difference from the taste evaluated under the condition with the eyes open. In addition, the extent to which the taste imaged from the color of the container matches the actual taste of the beverage was rated on a 7-point scale as "harmony." As a result of the experiment, it was found that the color of the container both strengthened and weakened the taste of the beverage compared to the standard, regardless of the color of the beverage itself. For example, yellow enhances sourness, pink enhances saltiness, and green enhances sweetness (Fig. 2). Harmony between yellow and sourness (Fig. 3) was high, and that between green and sweet was low, suggesting that the degree of harmony between color and taste is related to the enhancement or reduction of taste intensity. it was done. However, the degree of harmony between pink and saltiness was moderate, indicating that color-taste harmony is not the only requirement for container color to emphasize taste intensity.Figure 2: Difference between each color condition and standard. The standard taste intensity is set to 0, and the upper side of the horizontal line indicating 0 indicates taste enhancement, and the lower side indicates taste reduction. Figure 3: Harmony of color and taste under each color condition. Positive values harmonize, negative values disharmony. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals (Note 1).

This study suggests that the color of the container does not enhance or weaken a particular taste in the same way for all beverages, but rather that the sour beverage tastes more sour when sipped in a yellow container. was found to affect the intensity of specific flavors in beverages. In the future, for example, if you use a pink container that emphasizes the salty taste, you can feel a strong salty taste with a small amount of salt, leading to the effect of reducing salt intake. . (Note 1) 95% confidence interval: A range within which the true value is included with a probability of 95% when estimating the true value from the measured value. Title: Changes in taste intensity of beverages depending on container color Authors: Kazuya Okada, Makoto Ichikawa Journal name: Vision, Vol.33, No.3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24636/vision.33.3_117

![[Breakthrough infection report] 40.3% answered that they felt that the vaccine was “ineffective”](https://website-google-hk.oss-cn-hongkong.aliyuncs.com/drawing/article_results_9/2022/3/28/f9869be7ca5094f3e2ff937deaf76373_0.jpeg)

![[Compatible] iPhone 13 original smartphone case can be created! Started selling at smartphone lab that creates original smartphone cases](https://website-google-hk.oss-cn-hongkong.aliyuncs.com/drawing/article_results_9/2022/3/28/d6ecdfada565177ebd7562b3ea10c20c_0.jpeg)